In my daily work, I usually concentrate on building CI/CD pipelines, designing cloud infrastructures, monitoring these systems, and developing data pipelines. However, last week brought an exciting change from my typical routine as I ventured into the realm of software engineering principles, particularly “SOLID” and “IDEALS”.

In this blog post, I want to share my newfound understanding of SOLID. Following that, in the next article, we’ll learn about the IDEALS principle. The SOLID principle is a potent concept that can substantially improve the quality and robustness of your application code. It serves as a guiding light for software engineers striving to elevate their work’s standards, ultimately fostering a more dependable and maintainable codebase. So, let’s dive into the world of SOLID principles and see how they can improve your software development.

⚡ Tl;dr

- This post is written for junior to middle-level engineers.

- This article is specifically tailored for backend, SRE, and DevOps engineers who are embarking on their journey into the world of software architecture and design patterns.

- I will provide Python examples for all five principles to illustrate their application.

Why is clean code so important?

Before we jump into SOLID principles, let’s discuss why writing good code matters. You might be thinking, “Does anyone really care as long as the project works?” After all, some folks are okay with code that’s less than stellar, just saying, “Hey, it works, right?” However, rest assured, there’s more to it, and in this intro, we’ll delve into why crafting good code is a significant matter.

Okay, let’s break it down. We all get it, bad code is a downer for us developers. But let’s be real, under tight deadlines and high-pressure situations, we’ve all been guilty of creating code chaos at times 😳. Reflecting on my year in the trenches, here’s why I’ve come to appreciate clean code:

-

I often spent more time trying to decipher and fix code than actually creating it. Clean code is like a breath of fresh air because it makes me eager to breathe in and understand the whole software logic. Plus, it’s a breeze to enhance.

-

You’ve likely come across code that gives you a hard time when you attempt to extend it. Indeed, it’s not enjoyable.In the fast-paced world of agile development, you need code that’s ready to roll with the punches when client demands and tech stacks change.

-

Hunting for bugs isn’t anyone’s idea of a good time, especially when the code resembles a tangled mess. It can take ages to pinpoint the issue, and fixing errors in unreadable code can spawn even more gremlins.

-

Simplicity makes it straightforward to grasp the logic, reducing the chances of overlooking important test cases. This makes it easier to isolate for testing purposes, allowing you to focus on specific functionality without the need for extensive setup or mocking.

Karma strikes back!

Much like the concept of karma, the results we obtain in code quality are often a reflection of our initial efforts 💫. That’s why it’s essential to begin with clean code from the very beginning. Moreover, SOLID principles can be instrumental in maintaining code cleanliness and elevating overall code quality.

What is SOLID?

The SOLID principles were created by the famous American Software Engineer Robert Cecil Martin , affectionately known as “Uncle Bob” and constitute a pivotal foundation in the realm of software engineering.

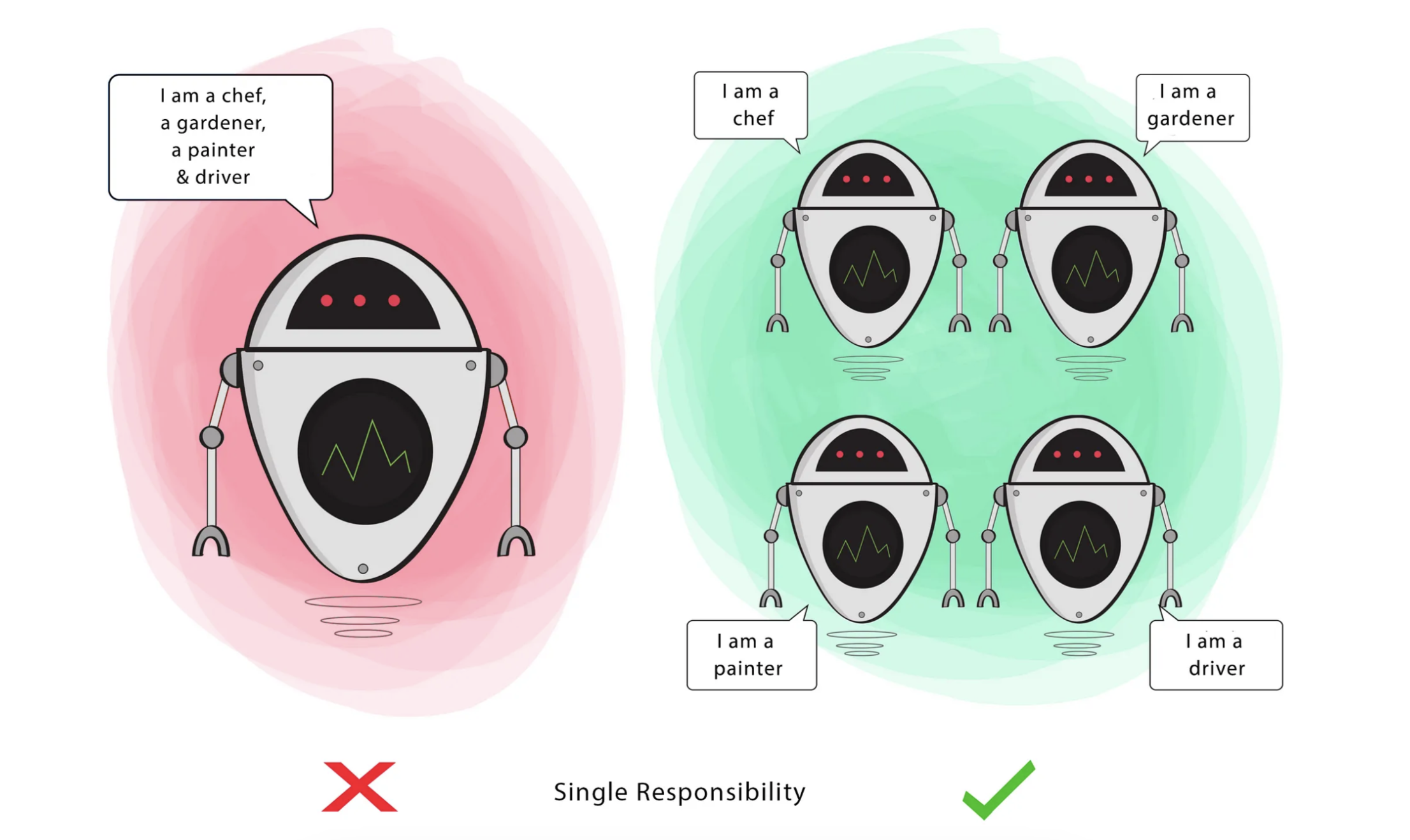

Single Responsibility Principle

SRP means that each part of your code should do just one specific thing or have one clear job. It keeps your code focused and easy to understand. As Uncle Bob puts it, “A class should have one, and only one, reason to change.

Example: Violating SRP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class User:

username: str

email: int

def get_username(self):

print(f"my name is {self.username}")

def login(self, username, password):

if username == self.username and password == "password":

print("Login successful ✅")

else:

print("Login failed ❌")

The User class is responsible for multiple unrelated responsibilities: Providing a method to get the username (get_username) and handling the user login method. To keep SRP a class should have only one reason to change, meaning it should have a single, well-defined responsibility.

Example: Keeping SRP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class UserData:

username: str

email: int

def get_username(self):

print(f"my name is {self.username}")

@dataclass

class UserAuthentication:

user_data: UserData

def login(self, username, password):

if username == self.user_data.username and password == "password":

print("Login successful ✅")

else:

print("Login failed ❌")

UserData and UserAuthentication into distinct classes. This adheres to SRP by ensuring that each class has only one reason to change: UserData manages user-related data (e.g., username and email).

UserAuthentication is responsible for user authentication logic. This separation of concerns makes the code more maintainable and adheres to the Single Responsibility Principle.

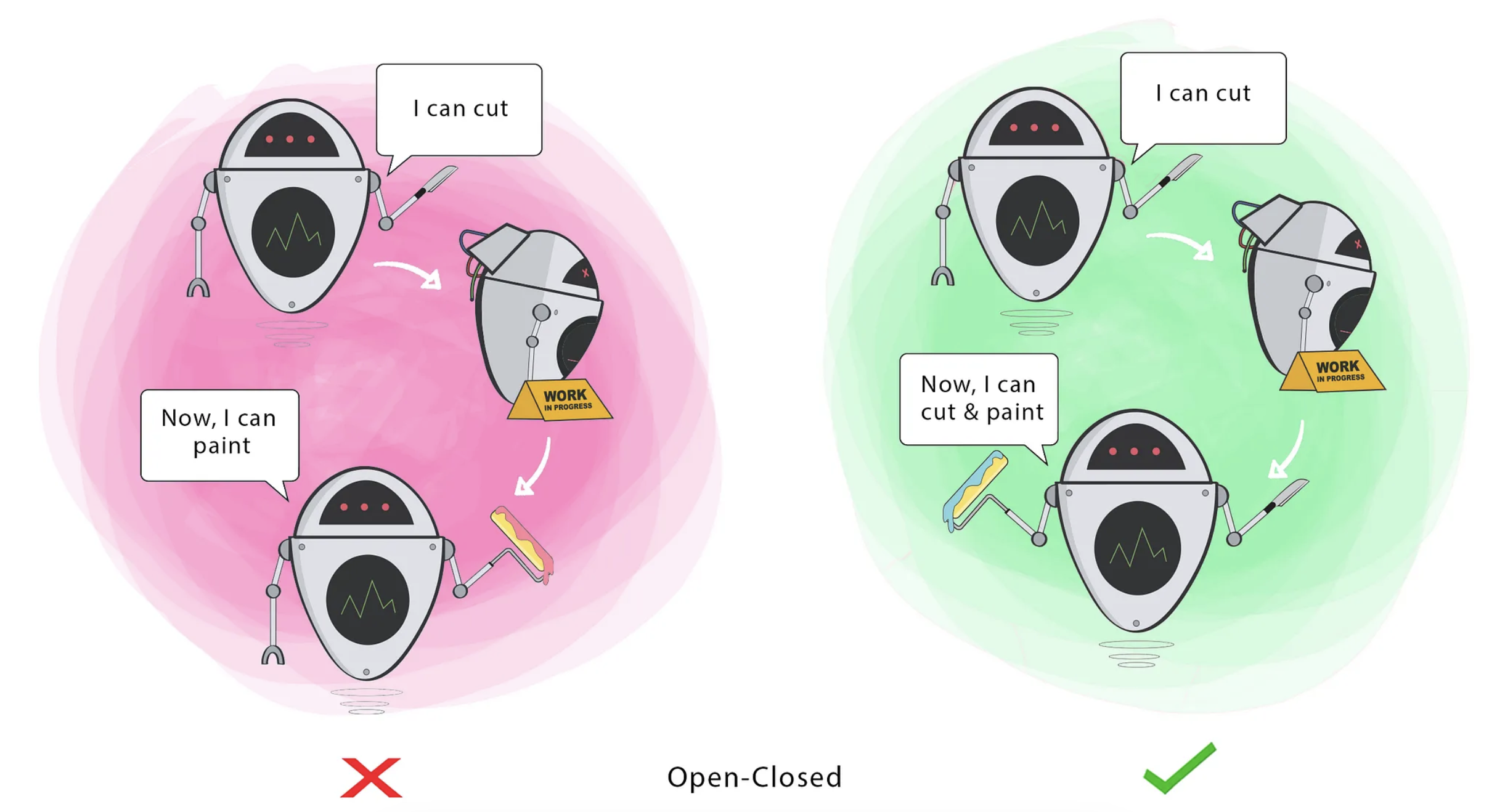

Open-Closed Principle

OCP means that once you’ve written a piece of code, like a class or a module, you should be able to extend its behaviour without modifying its source code. In other words, it’s “open” for extension but “closed” for modification. This helps maintain and improve software without risking unexpected side effects or breaking existing functionality.

Example: Violating OCP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class UserData:

username: str

user_type: str

def get_discount(self):

if self.user_type == "Basic":

return 0.1 # 10% discount for Basic users

elif self.user_type == "Premium":

return 0.2 # 20% discount for Premium users

else:

return 0.0 # No discount for unknown user types

class UserManager:

users: list = []

def add_user(self, user):

self.users.append(user)

def generate_invoice(self, user, discount, purchase_amount):

total_amount = purchase_amount * (1 - discount)

return f"Invoice for {user.username}: ${total_amount:.2f}"

To add a new user type (e.g. “PremiumPlus”), you would need to modify the UserData class by adding another conditional branch to the get_discount method. This means you have to change existing code when extending the system.

The generate_invoice method in the UserManager class also relies on the specific user types (“Basic” and “Premium”) and their corresponding discounts. If there is a new user type, you have to modify this method to accommodate the changes.

Example: Keeping OCP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class UserData:

username: str

user_type: str

@dataclass

class BasicUser(UserData):

user_type: str = "Basic"

discount: float = 0.1

@dataclass

class PremiumUser(UserData):

user_type: str = "Premium"

discount: float = 0.2

class UserManager:

users: list = []

def add_user(self, user):

self.users.append(user)

def generate_invoice(self, user, discount, purchase_amount):

total_amount = purchase_amount * (1 - discount)

return f"Invoice for {user.username}: ${total_amount:.2f}"

Open for Extension: BasicUser and PremiumUser extend the UserData class. These classes include the discount information as part of their attributes. This allows for easy extension to accommodate new user types without modifying the existing code.

Closed for Modification: We don’t need to modify the existing UserManager or UserData classes when adding new user types (e.g. “PremiumPlus”) or changing discount values. This demonstrates that the code is closed for modification.

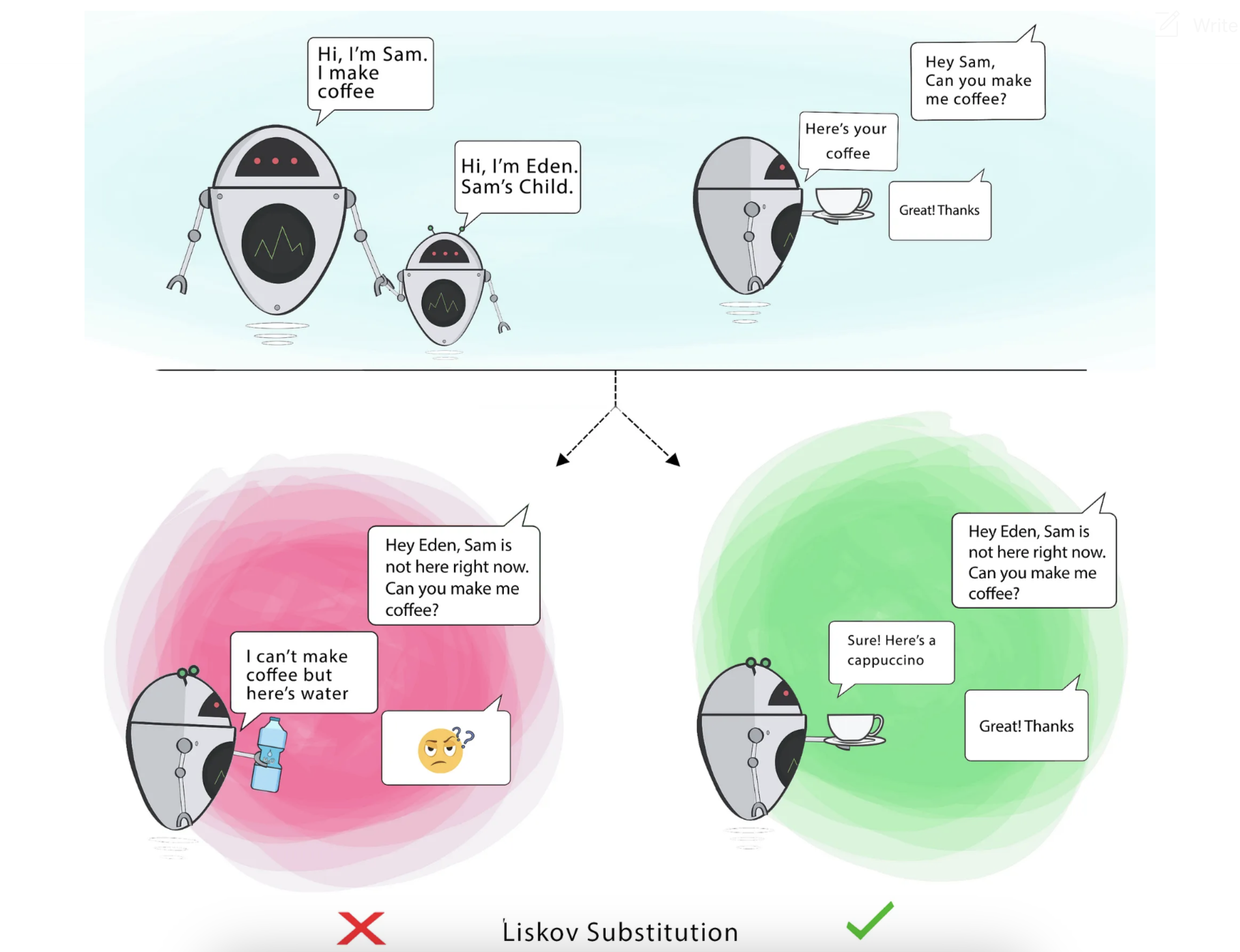

Liskov Substitution Principle

LSP says when a child class can’t do the same things as its parent class, it can lead to bugs. Inheritance should ensure the child class can handle the same requests and produce similar results as the parent class. This principle aims for consistency to prevent errors when using either the parent or child class.

Example: Violating LSP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class CoffeeMaker:

username: str

drink_type: str = "coffee"

def make_coffee(self):

print(f"{self.username} is making {self.drink_type} for you...")

@dataclass

class CappuccinoMaker(CoffeeMaker):

def make_coffee(self):

print(f"{self.username} cannot make coffee but can give you WATER...")

In the CoffeeMaker class, there’s a method make_coffee that makes coffee based on the drink_type attribute, which is set to “coffee” by default. In the CappuccinoMaker class, there’s also a make_coffee method.

However, in this subclass, the behaviour of the method has been changed. It states that the CappuccinoMaker cannot make coffee and gives you water, which is inconsistent with the expected behaviour of a “coffee maker.”

Example: Keeping LSP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class CoffeeMaker:

username: str

drink_type: str = "coffee"

def make_coffee(self):

print(f"{self.username} is making {self.drink_type} for you...")

@dataclass

class CappuccinoMaker(CoffeeMaker):

drink_type: str = "cappuccino"

def make_coffee(self):

print("1: coffee or 2: cappuccino")

input1 = input()

if input1 == "1":

print(f"{self.username} is making {super().drink_type} for you...")

elif input1 == "2":

print(f"{self.username} is making {self.drink_type} for you...")

else:

print("error: select the number")

Both CoffeeMaker and CappuccinoMaker share a common interface, i.e., they both have a make_coffee method. The CappuccinoMaker class extends the CoffeeMaker class by inheriting from it and overrides the drink_type attribute. This is a valid and expected behaviour within the LSP. When you create an instance of CappuccinoMaker and call its make_coffee method, it behaves as expected, making a cappuccino.

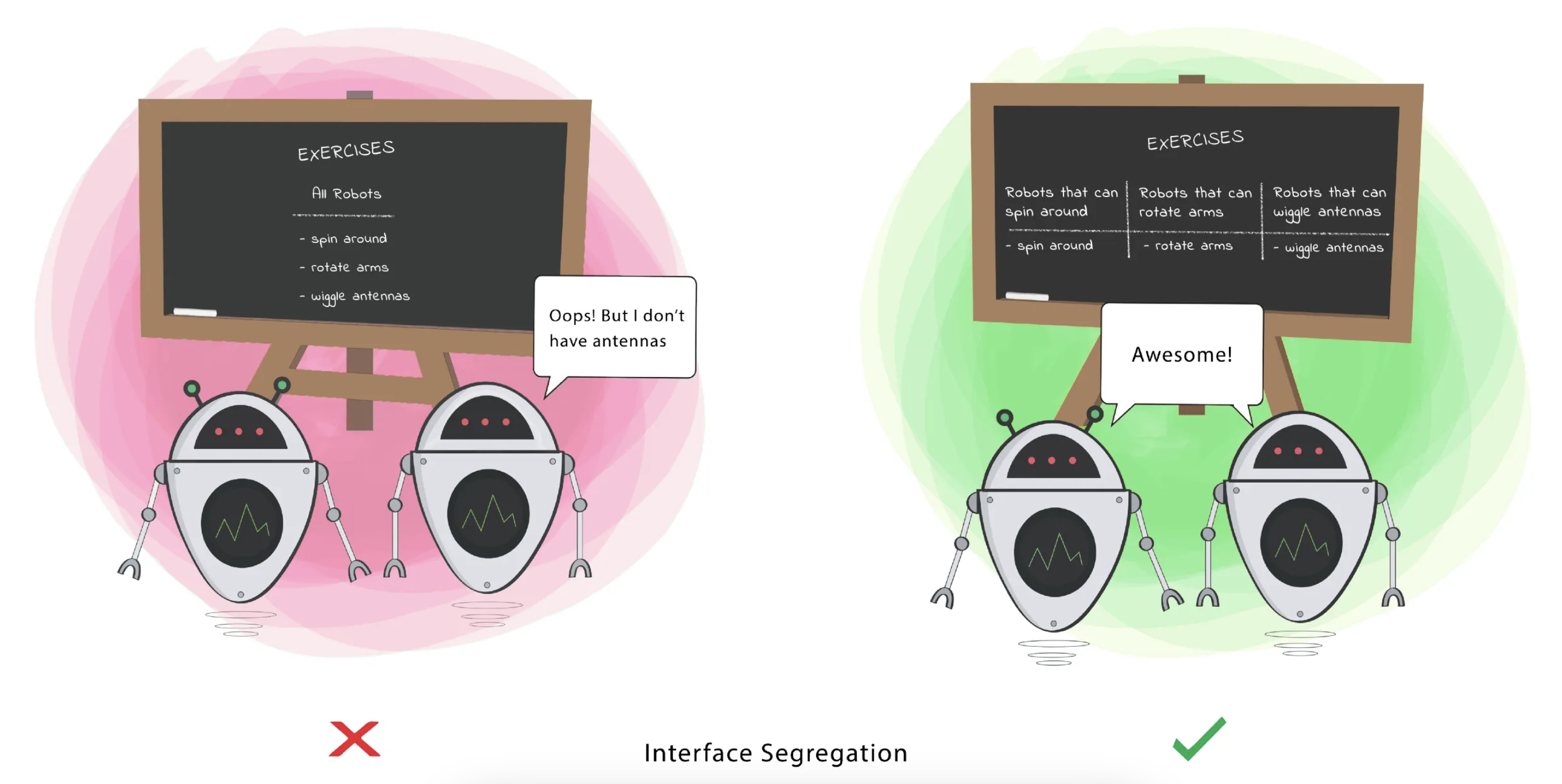

Interface Segregation Principle

Clients should only be exposed to methods they require. A class should execute only the actions necessary to fulfil its designated role. ISP suggests keeping interfaces small and focused. It advises against forcing classes to implement methods they don’t need.

Example: Violating ISP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class MultifunctionalDevice():

def print_document(self, document: str):

pass

def scan_document(self, document: str):

pass

class BasicMultifunctionalDevice(MultifunctionalDevice):

def print_document(self, document: str):

print(f"Printing: {document}")

def scan_document(self, document: str):

print(f"Scanning: {document}")

In this non-compliant example, we have a single interface MultifunctionalDevice that includes both print_document and scan_document methods. This violates the ISP because not all devices implementing this interface may need both printing and scanning capabilities.

Example: Keeping ISP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Printer():

def print_document(self, document: str):

pass

class Scanner():

def scan_document(self, document: str):

pass

class BasicPrinter(Printer):

def print_document(self, document: str):

print(f"Printing: {document}")

class BasicScanner(Scanner):

def scan_document(self, document: str):

print(f"Scanning: {document}")

class MultifunctionalDevice(Printer, Scanner):

def print_document(self, document: str):

print(f"Printing: {document}")

def scan_document(self, document: str):

print(f"Scanning: {document}")

There are separate interfaces Printer and Scanner, and classes BasicPrinter and BasicScanner that implement only the methods relevant to their respective interfaces. The MultifunctionalDevice class implements both interfaces.

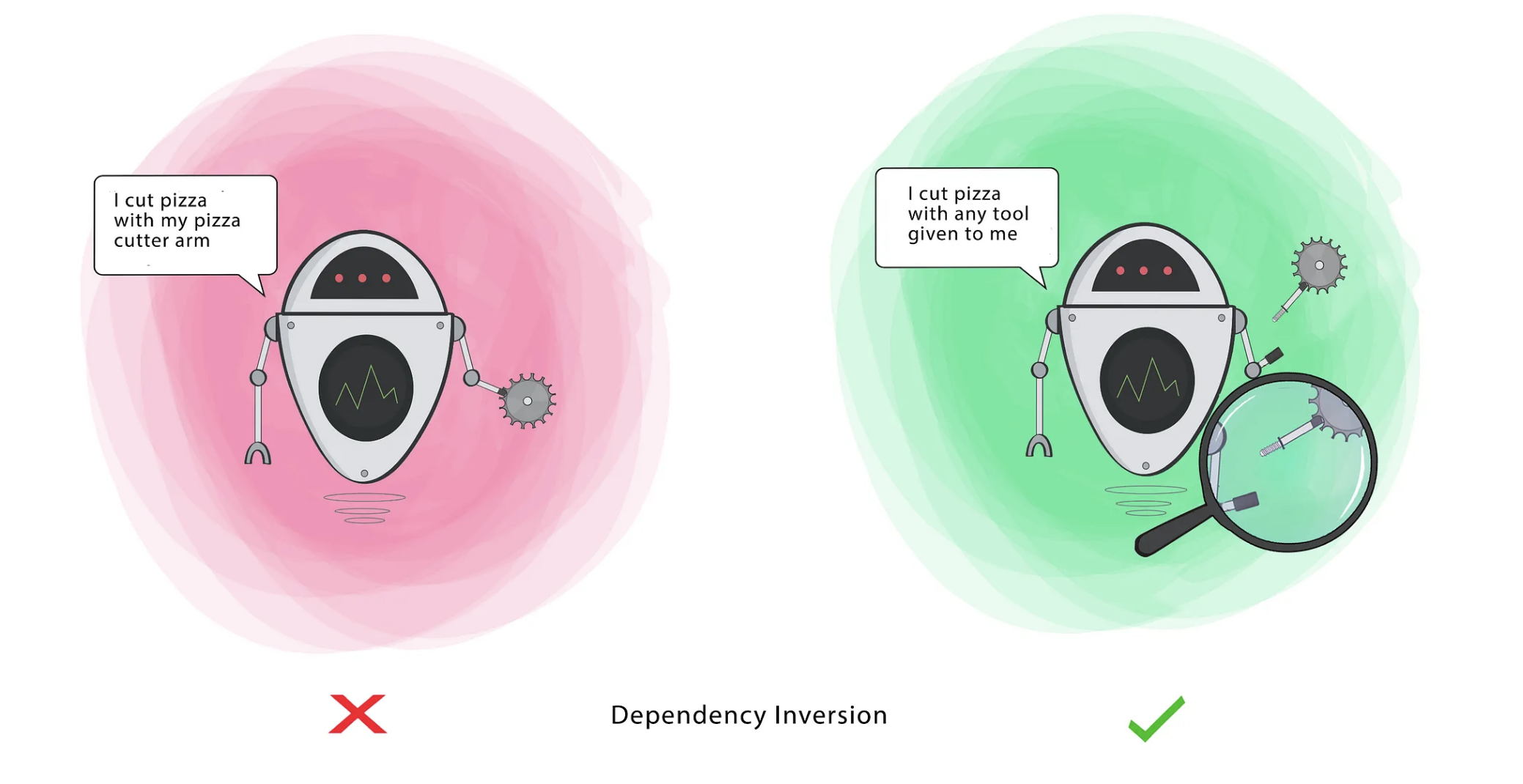

Dependency Inversion Principle

High-level modules should rely on abstractions, not directly on low-level modules. Abstractions should not be influenced by the details and instead, the details should depend on the abstractions.

Example: Violating DIP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class CPUMonitoring:

def check_cpu_status(self):

print("Checking CPU usage...")

@dataclass

class MemoryMonitoring:

def check_memory_status(self):

print("Checking memory usage...")

@dataclass

class MonitoringSystem:

cpu_monitor = CPUMonitoring()

memory_monitor = MemoryMonitoring()

def perform_cpu_check(self):

self.cpu_monitor.check_cpu_status()

def perform_memory_check(self):

self.memory_monitor.check_memory_status()

The MonitoringSystem directly depends on the concrete implementations of CPUMonitoring and MemoryMonitoring. This violates the DIP because high-level modules should not depend on low-level modules; instead, both should depend on abstractions.

Example: Keeping DIP

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class MonitoringService():

def check_status(self):

pass

@dataclass

class CPUMonitoring(MonitoringService):

def check_status(self):

print("Checking CPU usage...")

@dataclass

class MemoryMonitoring(MonitoringService):

def check_status(self):

print("Checking memory usage...")

@dataclass

class MonitoringSystem:

monitoring_service: object

def perform_check(self):

self.monitoring_service.check_status()

The MonitoringSystem depends on the abstract MonitoringService interface, allowing different monitoring services (CPUMonitoring and MemoryMonitoring) to be easily plugged in without modifying the high-level module.

Principles for Microservice Design

While SOLID principles are essential for Object-Oriented Design (OOD) architecture, it’s important to note that not all of them directly translate to microservice-oriented architecture (MOA), and vice versa. Moreover, there are entirely new principles unique to microservices. In the next article, we’ll explore these “IDEALS” (Principles for Microservice Design). Stay tuned for more insights!